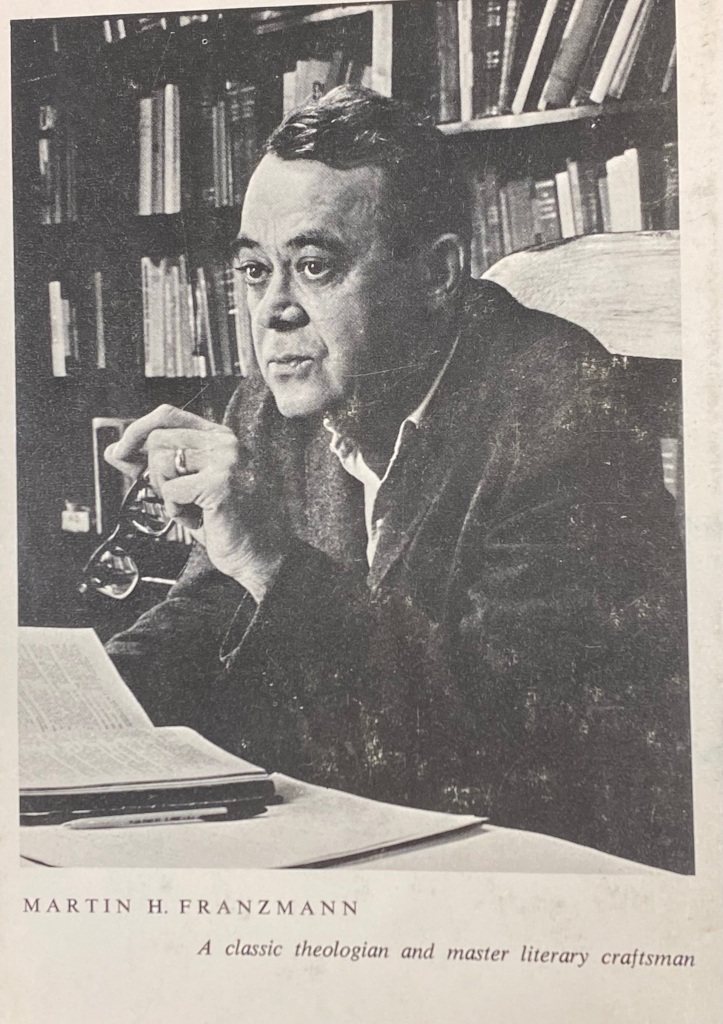

On this day in 1976, the day the church was singing how glad one can be when going to the house of the Lord, Martin Franzmann fell asleep in Christ. As this March 28th coincides not with Laetare Sunday but with Holy Thursday, I offer up a sermon Franzmann composed on a little line from Mark’s gospel which took place on the night our Lord was betrayed, a line about the man who fled naked. More than perhaps any other theologian, Franzmann has taught me that Christ does not deal in half measures. He goes fully to the cross, comes fully out of the tomb, and calls us to follow fully in his wake. My prayer is that during these most holy days we would not be the spectators Franzmann rightly calls out, but the full witnesses our Lord calls us to be.

THE YOUNG MAN WHO FLED

(Lent)

And there followed Him a certain young man, having a linen cloth cast about his naked body, and the young men laid hold on him. And he left the linen cloth and fled from them naked. Mark 14:51, 52

Some have supposed, and it is a very plausible supposition, that the young man mentioned in these verses is St. Mark the Evangelist himself; that St. Mark is here putting his signature to his gospel. If that is so, St. Mark is recording his own shame, and he is not the only inspired writer to do so. The early church preserved for us the tradition that the Gospel According to St. Mark is the record of the preaching of St. Peter, who in his preaching obviously did not spare himself. The Gospel that reflects his preaching is as unsparing as any in its portrayal of his weaknesses, his misunderstandings, and his denial; in fact it omits some things creditable to St. Peter which St. Matthew records. St. Paul himself, too, tells us that he persecuted the church, and does so that he may glorify the grace of his Lord the more. St. Mark, then, belongs to that goodly fellowship who sought not their own glory but Another’s, who had lost themselves in the wonder of the forgiving love of the God who had met them in Jesus, who is the Christ. What they write is not of themselves or for themselves. It is written for our learning.

The young man who fled learned something important that night on which, whether from youthful curiosity or whatever motive, he followed Jesus and His disciples from afar when they left the Upper Room for the Garden of Gethsemane. He wanted to look on, to see what would happen. He learned that you cannot be a spectator of the Lord Jesus Christ; you cannot follow from a distance and look on. You are involved one way or another as soon as you confront Him.

He learned the less, partly at least. The full lesson did not come easy, not even for the men whom we now call Saints with a capital “S.” The young man, John Mark, had promise. St. Paul took him along on the missionary journey, the first one, that was to carry him through Cyprus and into Asia Minor. St. Mark did well enough on Cyprus, apparently, amid the familiar pattern of his Jewish life, in the preaching in the synagog of the Diaspora. But on the starkly Gentile coasts of Asia Minor his courage failed him once more, and again he sought to follow his Lord from afar, as a spectator, from his mother’s house in Jerusalem. When Barnabas wished to take him along on the second missionary journey, St. Paul objected so violently that he and Barnabas quarreled and separated. Barnabas took his cousin Mark and went once more to Cyprus. We lose sight of him for some years after that. Somewhere in those years he learned those lessons fully. When next we hear of him, he is a fellow worker and a comfort to that fighter of the good fight, St. Paul, who bespeaks a welcome for him from the good people of Colossae. And when, again some years later, St. Paul summons Timothy to Rome that he may see him before he dies, he bids Timothy bring Mark with him and pays him the good workman’s tribute: “For he is profitable to me for the ministry.” The Christian who could thus confidently be summoned to Rome to be present at the execution of a Christian, not without risk to himself, had ceased to be a spectator and had become a witness. Except for an affectionate word from St. Peter we know nothing more of him. Later tradition has it that he made a good end and witnessed with his blood to the Lord, whose life he found the grace to pen.

The Lord Jesus Christ wants no spectators; St. Mark has taught us this in these two verses. We learn it everywhere in Scripture. Zacchaeus, who “sought to see Jesus who He was,” was not allowed to remain in this spectator’s perch in the sycamore tree. Jesus confronted him, and confronted him with a decision: “Make haste and come down, for today I must abide at thy house.” The Lord Jesus Christ tolerates no spectators. You are either for Him, or you are against Him. He not only hung on the cross in space between two malefactors; He drew a sharp furrow of life and death between them. The one reviled Him; the other said, “Remember Thou me!”

This lesson comes hard to our comfortable Christianity. We six-to-the-padded-pew disciples have blurred the line of the either-or; we grow uneasy at the fact, the completely obvious fact, that if we are involved with Jesus Christ at all, we are totally involved. “With the heart man believeth,” and “heart” in Biblical language is the whole man—his mind, his feelings, his will, and all that is within him. If some cynical joker, disgusted at our parochial squabbling, were to write over the church door, “Fighting Room Only,” he would be telling the sober truth albeit unconsciously. To believe on the Lord Jesus Christ does not mean only that we have become acquainted with a “catechismful” of facts about Him; it means that we have been drawn into the live momentum of a life that was lived to destroy the works of the devil. And there is fighting room only. “Fight the good fight of faith, lay hold on eternal life” is not just something that lends solemn pathos to the confirmation service; it is written over our whole life. Every minute brings a decision for or against Christ, and the decision involves a struggle and a fight.

If this begins to sound like overstrained rhetoric, let us put it to the test of fact. What happened the last time we were in church? When “In the name of the Father and of the Son and the Holy Ghost” was pronounced to us, we were in the presence of almighty God. How long did we stay there? Did we loll our way through the Common Service, or did we fight our way through, making the hard decisions against the distractions from within and without? Did we confess our sins, or did we recite the Confession of Sins and pass off our wrong decision, the decision not to trouble ourselves too much this morning about the Lord Jesus Christ but blame the “cold formalism” of the liturgy, that beating heart of Christendom? Did we fight for the Word, resisting the enemy, who is always on the snatch for it, or did we let it roll over us? Were we spectators or were we there, with the Lord Jesus Christ?

Whether we put it into words or not, most of us believe in our hearts that the decision was somehow easier in the heroic days when there were stakes to be burned at and lions to be thrown to. Our days are soundproofed against leonine roarings, and our temperatures are a genteel and uniform 72, thermostatically controlled. Perhaps; but the noises would grow, and the temperature would rise if we began making some little decisions, on the spot, like not letting the next dirty story pass; like not smiling indulgently or joining in, the next bit of greasy anti-Semitism that meets us, or the next calm and deadly cold assumption that the Negro is the inferior of the white man. Or we might try telling the next mealy moralist we meet, the next “do well, and all’s well” gentleman that strikes up a “religious” conversation with us, the whole bitter truth, for his good.—Life would not be so simple anymore, but it would be a Christian life, with the first syllable, “Christ,” spelled out upon it, and we should cease being spectators and become witnesses ready for the lions and the stakes, if they come. Amen.

Martin Hans Franzmann, “The Young Man Who Fled,” in Ha! Ha! Among the Trumpets (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1966), 46–50.